My Automotive & Mobility colleague, Dania Rich-Spencer, discussed the importance of building consumer trust in self-driving vehicles to drive adoption in a recent blog. One of her key conclusions was that “it is imperative that companies understand the factors that influence how people come to trust autonomous vehicle technology.” As I was reflecting on this premise and other related conversations, I started to think about similar situations in our lives where trust is a key factor to accepting change and adopting new behaviors. While we are grappling with the risks and implications of trusting a new technology that holds the promise of autonomously driving humans without their intervention, the process of letting go and giving up control—a core tenet of trust—is a familiar human experience. Of course, the bar is extremely high for self-driving vehicles because, at its highest level of autonomy (Level 5), “letting go and giving up control” to the technology can have life and death implications, something we typically only afford to humans. Understanding how we build the highest level of trust among humans may, therefore, be the key to understanding how we can build trust between humans and self-driving vehicles.

“Mom, Dad, May I Have the Car Keys?”

Any parent of teenage children can remember the day when their child asked them for the car keys to drive by themselves for the first time. Saying “yes” was scary and nerve-wracking and probably elicited a slew of silent prayers as parents watched their child drive off alone, hoping and trusting that years of teaching, training and experience had helped their child develop enough muscle memory and good decision-making to drive safely and responsibly on their own. Of course, the first drive was not going to be a spring break road trip but a short trip to a friend’s house three blocks over in broad daylight. Next came driving at night, then when it rained and, eventually, through a severe storm.

This was also most likely not the first time when a parent was faced with a choice to trust—or not—in the abilities of their child. Think about a child or a young family member who learned how to swim. Similar situation: after dozens of hours of lessons and practice came the day when a parent had to make a careful determination about the readiness of the child to swim on his or her own. Most likely, this decision was made while the parent kept a watchful eye over the child, only allowing them to swim within a safe distance away.

Just thinking about these two examples illustrates how humans develop trust among each other in situations that involve life and death decisions: it’s a process that happens over time and involves many little steps taken one at a time. And while a child’s ability to learn how to swim or ride a bike or drive a car may be good indicators of his or her abilities to responsibly act in risky, challenging situations that could result in harm or worse, each new situation is approached with its own criteria and requirements to build trust.

In this sense, the process of learning how to trust self-driving vehicles may be similar to the human experience of learning how to trust that a child can swim or drive on his or her own. At some point, engineers and consumers will have to trust that the technology has developed enough “muscle memory” to make good decisions and safely chauffer passengers to their destinations. This means fully self-driving vehicles will have to be able to react correctly not only in predictable situations but also in unforeseen circumstances, assess evolving dangers correctly (such as when the road is getting too slippery and the vehicle needs to slow down) and pull over when necessary (such as when sirens are blaring from an oncoming police car, ambulance or fire truck). In other words, reactive behavior will be just as important as proactive behavior.

The Complexity of Building Human Trust in Self-Driving Vehicles

So, where are we in terms of trust when it comes to self-driving vehicles?

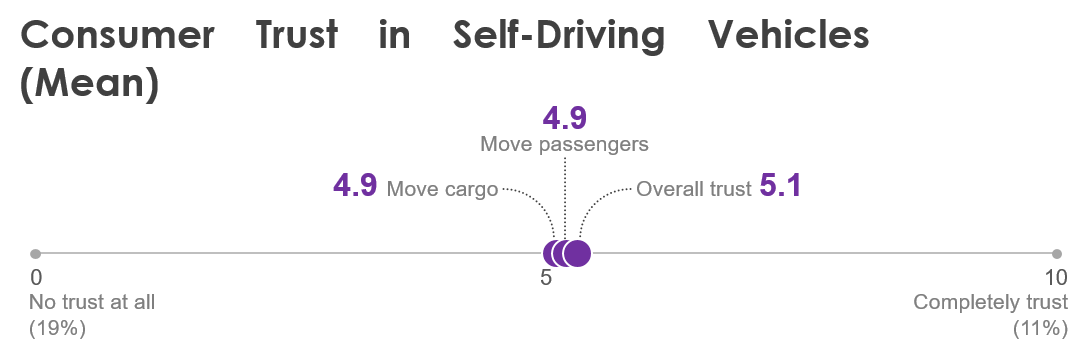

Our recent findings show we still have a long way to go. Earlier this year when we asked consumers about their level of trust in self-driving vehicles that require no human intervention, consumers rated their trust a 5.1 on a scale of zero to 10 where 10 meant they completely trust the technology.

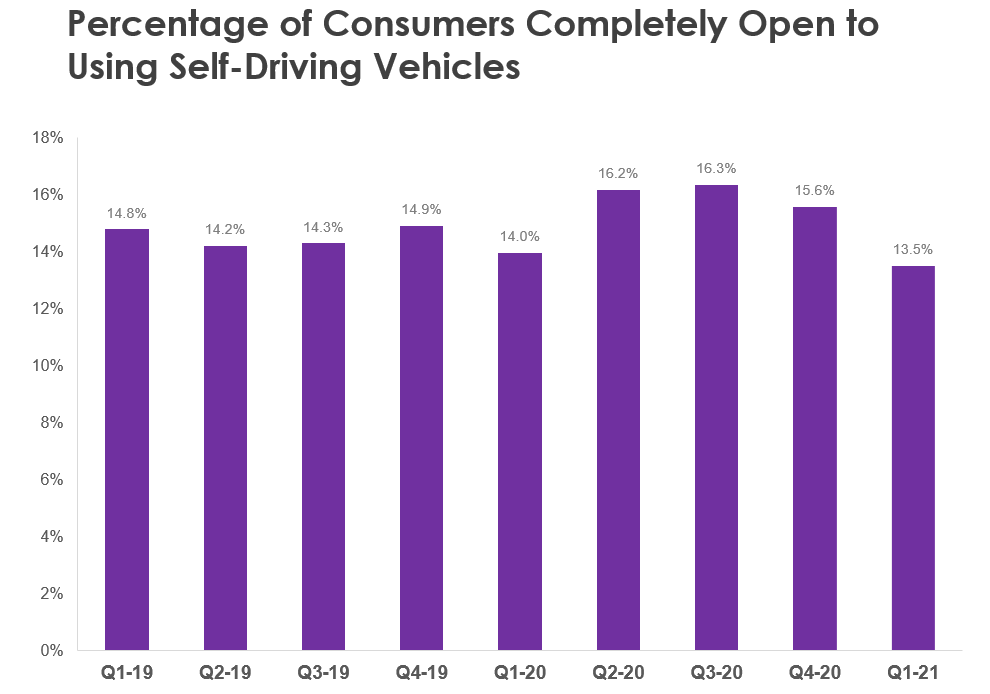

While this score may have indicated some cautious trust in the capabilities of self-driving vehicles, another question about the actual willingness to use such vehicles reveals a much greater level of hesitancy. When asked about their openness to using self-driving vehicles, we found that fewer than one-fifth of consumers said they were completely open to using self-driving vehicles. And this has consistently been the case for over two years.

In other words, while there is some consumer openness to and, in some cases, even excitement about the technology, self-driving vehicles will still have to demonstrate a level of proficiency much closer to the human driver before consumers will put their trust in the “seats” of an AV. Or, as it was put so eloquently in a 2004 white paper on Trust in automation: Designing for appropriate reliance by Lee & See: “Trust stands between the beliefs about the characteristics of the automation and the intention to rely on the automation.”

When it comes to navigating a vehicle, replicating the human experience and intuition isn’t easy and with every new advancement, AV makers discover new challenges and obstacles. Developing muscle memory is one of the hardest and most time-consuming things to do, as every athlete knows. Thomas Muller, CTO engineering and global practice, NextGen Services at Wipro, addressed this challenge and underscored the importance for AV makers to include human driver behavior data in their quest to build fully self-driving autonomous vehicle technology in a recent article:

Mueller said the value of human driver behavior will always outweigh that of the robot. He added: “This delta data of comparing a human driver who is actually driving day-to-day and comparing it to what the synthetic driver, which is getting smarter by the day, is the most valuable data there is. With a test driver sitting in an autonomous vehicle and doing nothing, the computer cannot compare how a human can handle a situation. So it will always behave like a robot and not like a human.”

Conversely, we may also find that some human behavior will have to change or adapt to embrace a new self-driving vehicle reality, such as learning new “traffic rules” or interpreting new information that was not available or necessary when we were in control of the vehicle.

The Kiddie Pool and the Parking Lot

For now in AV development, we are at the “kiddie pool” or in a “parking lot” watching our youngsters take their first strokes or drives. In order for us to trust them on their own one day, they will have to demonstrate they are able to stand on their own feet at every step of the way. For AVs, this will mean the technology will have to demonstrate it has a solid grasp of its environment, it can handle typical driving situations with increasing difficulty and it can make the right decisions when it comes into dangerous or ambiguous situations. Additionally, AV makers will need to confirm the quality and design are up to everyday challenges and that the public infrastructure and environment upon which AVs rely (such as traffic lights and other autonomous, connected vehicles) are safe and reliable—which is a whole different topic and challenge unto itself. Before most consumers will set foot into a self-driving vehicle, they will most likely want to see independent proof that the vehicle has passed all safety tests.

For example, this could include future test drives to be done remotely by watching a self-driving vehicle in real-time through a camera. For some people, it may take a long time before they fully trust a self-driving vehicle, preferring to stay “in the shallow end of the pool” for awhile—for instance, only occasionally taking a ride in an autonomous bus or taxi. Only if the self-driving vehicle has earned enough trust with the passenger in simple situations will the person in question be willing to let it “swim further out.” On the other hand, allowing passengers to have some level of control, such as deciding which roads to take, may be an easy way to build consumer trust and ease concerns without altering the overall experience.

Lifeguard On Duty

While I am sure we, as a society, will learn to trust self-driving vehicles one day, we may also decide to always have a “lifeguard” on duty. As much as we know that we have to let a child swim on his or her own one day, we always feel a little better if there is a lifeguard around because we know that humans are not perfect and accidents can happen. And in our modern-day life, we know the same is true for technology. While autonomous vehicles can help to dramatically reduce the number of vehicle deaths caused by human error, we have yet to allow technology to become the sole operator in life-or-death situations. For every rocket, there is a mission control. For every auto pilot, there is a human pilot. For every intensive care machine, there is an intensive care nurse.

This creates an opportunity for new revenue streams for manufacturers and service providers, the first examples of which have started to pop up, including an announcement by Visteon in 2020 to “add remote-control capabilities to its autonomous-driving platform.” Having an AV “lifeguard” will likely also help speed up adoption: consumers may come to trust AVs earlier or more widely than they otherwise would have if they know there is a trusted source of help available as a backup should the AV technology encounter an error.

As a company whose mission it is to help brands translate human behavior into ideas that make the world work better for people, Escalent is excited about the prospect of fully self-driving vehicles. We look forward to working with our clients on understanding the factors that influence how humans come to trust one another and to translating those learnings into effective strategies for building trust between humans and self-driving vehicles.

If you would like to learn how we can help you build self-driving vehicles that are trusted by consumers or want to know more about our capabilities, please send us a note.

Methods Disclosure

Escalent interviewed a national sample of approximately 1,000 consumers aged 18 and older over a two week period each month from Q1 2019 to Q1 2021. Respondents were recruited from the Dynata opt-in online panel of US adults and were interviewed online. Quotas were put in place to achieve a sample of age, gender, income and ethnicity that matches the demographics of the US population. The data have a margin of error of 3 percentage points at a confidence level of 95%. The sample for this research comes from an opt-in, online panel. As such, any reported margins of error or significance tests are estimated, and rely on the same statistical assumptions as data collected from a random probability sample. Escalent will supply the exact wording of any survey question upon request.