Two recent JAMA headlines, Women’s Representation Among Lead Investigators of Clinical Trials in Oncology and Disparity of Race Reporting and Representation in Clinical Trials Leading to Cancer Drug Approvals From 2008 to 2018, spark debate about the diversity of both those participating and those running oncology clinical trials today.

In an era where racial and gender diversity is a hot topic across the country, it is no surprise that issues of underrepresentation also extend to oncology. And these issues are getting serious, scholarly attention as evidenced by these JAMA articles focused on diversity in oncology clinical trials.

Gender disparity rears its ugly head when looking at clinical trial investigator demographics…

Currently, almost one-third (32%) of US oncologists are women, so, naturally, one would expect that this ratio would be reflected in the gender of lead investigators involved in oncological trials. However, this JAMA article points out that male investigators outnumber their female colleagues disproportionately.

“The underrepresentation of women physicians and scientists may affect their own career advancement, but more importantly this may affect scientific discovery and patient care. Women physicians and scientists provide an enormous brain trust that is key to unlocking the biology of disease.”

— Julie K. Silver, MD, of Harvard Medical School in remarks to Cancer Network

…and issues in racial reporting and representation seemingly abound.

Just a week later in another JAMA article, authors revealed a plethora of issues around the participation rates of racial minorities as well as the reporting of results involving these groups. One-third of the trials neglected to report on patients’ race at all and in those that did, minorities were significantly underrepresented.

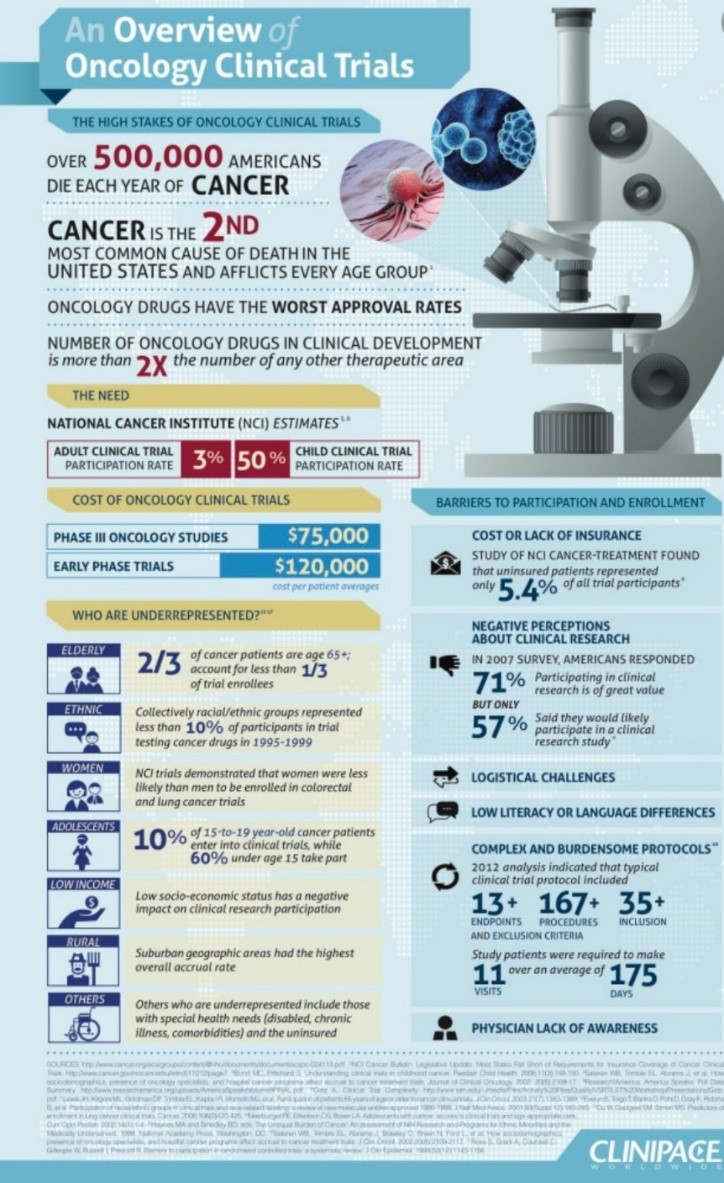

These issues are not new; a wonderful infographic prepared by Clinipace Worldwide provides an outstanding overview of the “state of the union” of oncology trials. While the data are not as up-to-date as the JAMA statistics, the story is still clear.

Racial and ethnic groups = <10% of trial participants from 1995 to 1999.

Racial and ethnic groups = <10% of trial participants from 1995 to 1999.

Women are less likely than men to be enrolled in colorectal and lung cancer trials.

The implications of this type of underrepresentation are profound. Trials represent opportunity for patients to access new and clinically meaningful medications. Trials also represent the opportunity for better understanding of the nuances of a disease or treatment, especially among smaller subgroups, and to the extent such nuance is not reflected in the study population, the volume of data and confidence in those data will be compromised.

“It’s important to recognize that this problem is there and this problem is persisting over the years.”

— Kanwal Raghav, author of the study and an oncologist at MD Anderson Cancer Center

These issues can’t be solved overnight, naturally, but it should trouble us all that the issue has persisted for so long. In today’s dynamic world of oncology, where the pipeline is literally exploding and there are almost too many clinical trials to count (ongoing and planned), it seems well past time to give this challenge the consideration and attention it deserves.

Awareness is the first step toward a diversity solution.

There are many, many variables impacting oncology clinical trial recruitment and participation, often intertwining and overlapping in such a way that it is difficult to tease out driving factors. However, at the very least, promoting awareness of these diversity pitfalls as a way of “shining a light” on the problem seems a sound beginning.

We need a holistic approach to tackling this problem, understanding both the “push” and “pull” around clinical trial recruitment and how to enhance diversity in the process from both directions. What are the roadblocks from the perspective of trial design and protocols that may differentially deter enrollment from underrepresented groups? Are there challenges around the oncologist-patient relationship and dialog in disseminating information about trials or encouraging patients to enroll in trials? Do the underrepresented groups have different attitudes or perceptions around clinical trials (or those who run them) that act as a disincentive to participate?

These are all avenues worthy of future exploration.

And they carry implications for how we approach conducting research. We conduct research to guide the design of clinical trials, including the appropriate patient populations to include. Researchers need to be sensitive to providing a true representation of the breadth of the relevant patient population and proactively include such criteria in screeners, if appropriate. Probes need to be built into discussion guides to better understand the criteria by which physicians decide to approach particular patients about clinical trial involvement and whether there is a selection bias impacting the flow of potential recruits. And we need to better understand how different groups may be more or less inclined toward participation and how to surmount any barriers to greater participation.

These are just a few of the ways in which we can strive to improve our approach. Again, awareness that there is a problem is indeed the first step.